Discovering life in death, & much in so little

- Kali Widd

- Jun 25, 2023

- 7 min read

Updated: Jun 26, 2023

Tantra is the philosophy of Totality, and how often, seeming dualities are simply 2 sides of the very same coin. In this essay, I explore how in death we can discover so much about life. I also unpack how how cities bursting with distractions and experiences can lead to a sense of emptiness, whilst living in a tiny farming village can lead to a full and abundant life:

When flashing through small rural villages on road-trips past, I would ponder, ‘How dull it must be to live in such insignificant little places, delightful though the countryside may be.’

A cosy blanket of smug superiority would then settle softly upon my patronising shoulders, and I would drive on appreciating having lived most of my life in vibrant, cosmopolitan cities like Durban, Johannesburg, Dubai, London and Cape Town.

Usually, I would then spend the rest of my trip fondly reviewing the places I’ve been blessed to call home, and the cat-cream smile would grow wider, crinkling the corners of my eyes, finally landing in my heart with a self-satisfied sense of having experienced a life well-lived.

I grew up just outside the lush, sub-tropical, palm-tipped fringes of Durban, whose mix of colourful people, cultures, religions, and races is as spicy as the Indian BunnyChow curries it’s renowned for. I loved Durban.

Next came my first grown-up job after graduating and travelling Europe, based in Johannesburg – Africa’s somewhat chaotic answer to New York’s famed melting pot. Here I was introduced to political activism and the fervent underground of ‘The Struggle.’ I loved Johannesburg.

Dubai’s jewel-coloured parrots, minarets and plaintive calls of the muezzins were a welcome relief from the eruption of violent crime preceding and following South Africa’s first democratic elections, and I revelled in the Arabian deserts and crystal-clear seas. Here I could leave my car engine and air-conditioning running whilst popping into Spinney’s for some provisions. It was liberating. I loved Dubai.

And of course, London was a rush! Although I felt like a country bumpkin come to town, I threw myself into everything the cultural life had to offer, spending all my disposable income on theatre productions, concerts, museums, ballets, operas, and big music events. I was in heaven. I loved London.

Cape Town is universally agreed to be the most beautiful city in the world, and that’s why it’s known as the Mother of all Cities. Very few can compete with spectacular Table Mountain, or the sumptuous wine lands and stunning beaches. It’s not worth even trying. I loved Cape Town too.

But until I moved to a tiny rural hamlet, I hadn’t spent much time remembering how lonely I would occassionally feel in these metropolises: how insignificant, isolated, anonymous, and lost I could be on weekends, when everyone else seemed to be spending time outdoors, or in trendy cafés with family and friends. I had forgotten sobbing my eyes out watching ‘The Lion King’ production on the West End because I was immensley homesick for Africa, or wondering if there was more to this hollow life than earning lots of money and buying tons of glittery things.

It was only after moving to Barrydale, in the Klein Karoo, on the Route 62, that it finally dawned on me just how completely wrong I’d been about the dullness of small village life. Oddly enough, it was through death that its rich depths were revealed to me.

I hadn’t been in Barrydale for very long when a terrifying fire broke out in the surrounding fynbos-clad mountains. Fynbos is meant to burn to the ground every 7 years in order to regenerate itself, phoenix-like, from the ashes. We hadn’t had a fire in 10 years, and so the sap was high. I could see volcanic flames shooting into the night sky from my front door, and panicking, packed for imminent evacuation. Seasoned ‘dalers would chuckle casually, telling me to stop fussing - the fire brigade, farmers, nature conservation and municipality were seasoned fire fighters, and they knew what they were doing, working 24-hour shifts in one powerful, collaborative team effort. The whole town rallied to provide food and water to our exhausted troops on the frontline, and even as ash rained down on our houses, nobody seemed particularly perturbed.

Back breaks were cut around the suburbs and farms, and sure enough, the wind changed, and the fire receded back into the mountains from whence it had come. Only then we heard the devastating news that one of our own had succumbed to smoke inhalation whilst fighting valiantly to hold the fire at bay. Nelio was a young father and proud part-time firefighter, and he’d recently informed his mother of his desire to become a full-time fireman. We all knew him from the OK Bazaars, where he was a much-loved shop assistant.

I don’t know who cried more at his memorial service: his family or me. Something about this young man’s sacrifice touched me to my core – and the way the whole village turned out to show its appreciation and respect, black and white alike. (South Africans who’ve lived through Apartheid will appreciate the poignancy of this.)

First, there was a slow vehicle drive-by past Nelio’s family’s home; next the fire-fighting helicopters flew in low formation over the roofs; then the police, ambulance workers and fireman paraded past the family seated on chairs in front of a red carpet, where all the guests walked to offer their condolences, and lay flowers. The local brass band played, and the preacher prayed with the people.

I sighed and thought, ‘That’s probably the last memorial I’ll attend for a while – after all, this is a small village with only a few thousand people.’ I was greatly relieved, because I didn’t know if my heart could again stand feeling so much for someone I barely knew. I was wrong.

A few months later, a beautiful young girl with great potential was tragically raped and murdered by her ex-convict stepfather, prematurely released from South Africa’s overcrowded prisons during COVID. Barrydale was utterly stunned. We occasionally experience minimal petty, opportunistic crime, but this kind of brutality is unheard of in our village.

Again, the community came together in a way that shattered my heart wide open. We were asked to gather in a large circle at sunset on a hill between the village and the township, and to bring candles. In the fading light, with flaming candles forming an inner circle on the ground, we held hands and sang, cried, mourned, and prayed together as one people, with one grief. I didn’t think my heart could take feeling all it was feeling.

And then came beloved Shane’s sudden passing from a catastrophic heart attack. Shane was our ‘unofficially elected town mayor,’ known and loved by absolutely everyone for his compassion and care for the underdog, as well as for his involvement in putting Barrydale on the map.

Furthermore, every Friday, the marginalised would gather on the stoep of his shop – the world-famous Magpie, which creates masterful chandeliers from up-cycled tin, glass, plastic, and beads – and there Shane would ladle out hot homemade soup, the one sure meal of the week for many. He was a devoted Quaker, and on the board of our local hospice and youth NGO. In fact, Shane was like superman, he was everywhere, all the time. His passing left a massive Shane-shaped hole in everyone’s hearts, and his memorial at the clinic bequeathed 2 unique benches affixed with dedicated plaques to his memory. We sang Amazing Grace.

Today, as I write this, I grieve the passing of Bridget, also known as Steffi, a delightful shop assistant at our OK Bazaars, who left us at the age of 39. Bridget was one of the first people to know me by name when I moved here. She asked me who I was, why I’d moved here, and demanded to know details about my life and my family. From that moment on, she never forgot my name, or my circumstances.

Bridget was the community’s Akashic Records: she knew absolutely everybody's name, including the farmers from the far-flung surrounding Karoo. Even if she wasn’t my cashier, she would call out, ‘Hellooooo Kali, hoe gaan dit met jou? Hoe gaan dit met jou dogter daar by Londen?’ ('Hello Kali, how are you? How is your daughter doing in London?') She in turn, would tell me about her son, who was competing in regional karate competitions. Our tradition was to share pleasantries and the latest news of our families.

You would never know to look at her that she was suffering from stage 3 breast cancer, or that she was on chemo treatment. She was always smiling, and today, the minister, who loved her like a daughter, said, ‘On her final journey to the hospital in Swellendam, and looking right through death’s door, she beamed and said to everyone in the ambulance, “There is so much hope.”’

The Christmas-cake NGK church was packed to capacity, with people of every hue, and from every walk of life. We all came together to pay tribute to a humble lady whose life had had an enormous, meaningful impact on thousands of people.

Here, in my small village, you matter. Everyone knows who you are, and everyone cares about who you are, even if they don’t like you very much! Our currency is not money, but relationships. We trade, swop, barter, and innovate where they may be a lack. We bicker and gossip yes, yet we also wave at one another, and greet each other – every.single.time.

The kids call all the adults ‘tannie’ and ‘oom’ out of respect ('aunt' and 'uncle'), and the men still politely give up their seats for a standing woman. Most tradesmen refuse to invoice call-out rates, and sometimes even refuse to charge altogether – ‘Ag man, dis niks, volgende tyd buy me a coffee,’ they’ll say, mixing up Afrikaans and English in the way tweetalige folk do.

When I was so ill, I couldn’t get up to cook for myself, thoughtful neighbours piled scrumptious meals upon my doorstep. My home overlooks 3 farms, and one of the farmers, who many call the dragon-lady, but who is really a sweetheart, told me to repay her amazing home-cooked lasagna with a double gin and tonic next time she gets sick. That’s how we roll.

A farming village moves at the pace of nature, and we’re afforded quality time to watch the seasons change, espy the smaller wild animals that share space with us, and appreciate the various light shows put on by the dramatic Karoo sky. The Milky Way gifts us nightly with diamonds, and the soil supplies us with abundance. We lack for nothing. We live to human-scale, with no traffic jams, road rage or lack of time to get things done at leisure.

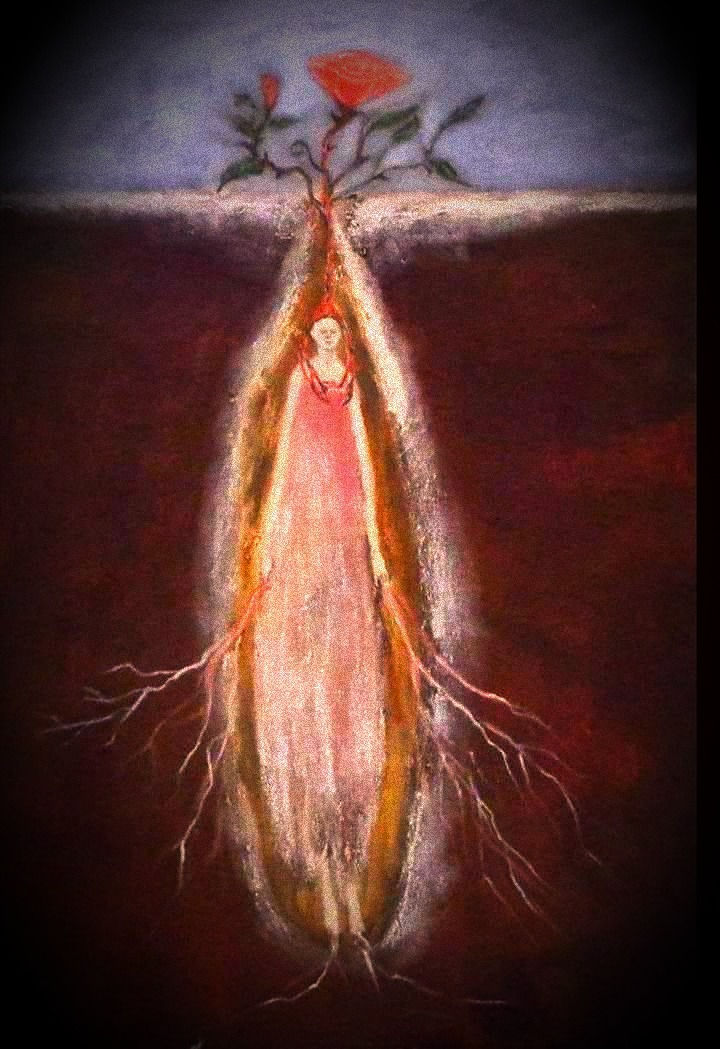

As the cycles of life, death, and birth turn through the years, I’m grateful I stopped speeding through miniature gems like Barrydale, and made the inspired decision to live out in the countryside. It's only here that I finally feel fully alive, planted, and rooted exactly as I am, precisely where I belong, within a close-knit community that will one day sing my name when my bones finally come to rest under this precious earth.

Comments